Let’s address the elephant in the oncology room: fungi.

More specifically, let’s talk about the compounds they produce – mycotoxins – and the alarming blind spot in modern medicine when it comes to their potential role in chronic disease, including cancer.

For decades, the dominant view within mainstream oncology has clung tightly to the Somatic Mutation Theory (SMT – the belief that cancer is the result of accumulated random mutations in our DNA. Anything outside that paradigm is often dismissed or ignored, no matter how compelling the evidence. Fungal involvement? Not even a footnote in the conversation for most oncologists.

But what if we’ve been looking at cancer through the wrong lens? And what if, in doing so, we’ve not only misunderstood the true origins of the disease but also overlooked a very real and measurable threat – mycotoxins, the toxic metabolic by-products of fungi that are known to suppress the immune system, damage DNA, and trigger chronic inflammation?

Even if you don’t accept the full implications of the Cell Suppression Theory that I propose – where intracellular fungal pathogens hijack cellular machinery to create cancer – there’s still an undeniable truth: mycotoxins are toxic, immunosuppressive, and inflammatory agents. And they may be a major missing piece in the cancer puzzle.

The Mycotoxin Problem: Hiding in Plain Sight

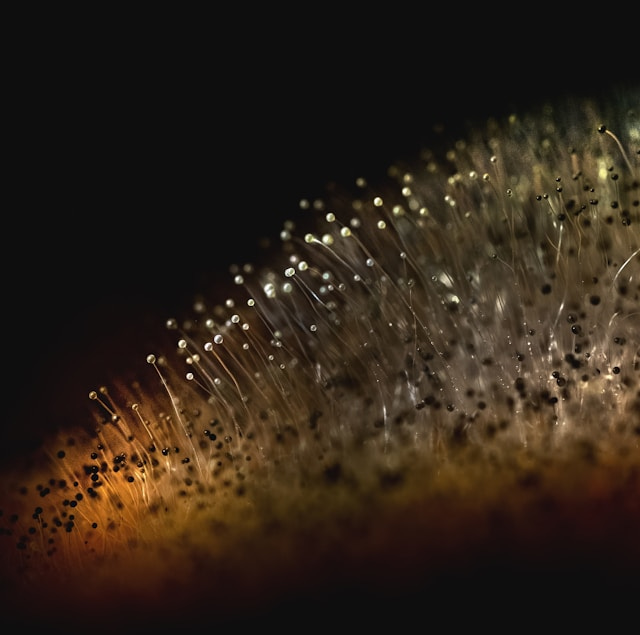

Fungi are everywhere. They exist in our environment, in our food, and even in our bodies. Under normal conditions, many of them are harmless. But certain species produce mycotoxins – secondary metabolites that can wreak havoc in the body.

These mycotoxins include, but are not limited to:

Aflatoxins: Found in contaminated grains and nuts, aflatoxins are potent carcinogens and are classified by the WHO as Group 1 carcinogens, meaning there's clear evidence they cause cancer in humans.

Ochratoxin A (OTA): Found in water-damaged buildings, coffee, and cereals, OTA has been linked to kidney toxicity, immune suppression, and DNA damage.

Trichothecenes (e.g., T-2 toxin): Produced by Fusarium species, these interfere with protein synthesis, leading to immune dysregulation and tissue damage.

Zearalenone (ZEA): An estrogenic mycotoxin that can disrupt hormonal balance, potentially playing a role in hormone-driven cancers.

Gliotoxin: Produced by Aspergillus fumigatus, this toxin is particularly dangerous due to its immune-suppressing capabilities.

And those are just the best-known culprits.

Why the Medical Establishment Still Shrugs

Despite the fact that many of these mycotoxins are scientifically validated to cause oxidative stress, DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and immune exhaustion, the topic is often dismissed as fringe in cancer circles. Why?

Because acknowledging fungal involvement in disease – especially a disease as complex as cancer – would require rethinking foundational assumptions. It would challenge the mutation-centric dogma that underpins most drug development and clinical protocols. And that is something few institutions are prepared to do.

But here’s the reality:

You don’t have to accept fungal infection as the cause of cancer to acknowledge that mycotoxins – whether from environmental exposure or internal fungal colonisation – may play a central role in creating the inflammatory terrain that cancer thrives in.

The Chronic Inflammation Connection

Chronic inflammation is now recognised as one of the key drivers of nearly every modern disease, cancer included. It’s the fire that keeps the disease engine running. And mycotoxins are known accelerants.

Consider this: exposure to certain mycotoxins has been shown to upregulate NF-κB, a key inflammatory pathway associated with tumor progression. Others inhibit mitochondrial function, and trigger the oxidative stress that damages cellular machinery. Some are even designed to suppress the immune response enabling fungi and the cells they invade, to evade immune detection – sound familiar?

This is no small influence. It’s not merely a trigger – it’s a perpetual feed-forward cycle where inflammation begets immune dysfunction, which begets more inflammation, DNA damage, and cellular mutation, all while placing incredible stress upon the immune system that ultimately reduces it’s capacity to function optimally.

Environmental + Internal Exposure: The Double Hit

There’s a common assumption that mycotoxin exposure is primarily environmental – mouldy buildings, contaminated food, or water-damaged homes. While this is certainly one source, few acknowledge the second, more insidious pathway: internal fungal overgrowth.

Fungal infections can persist quietly within the human body – often undiagnosed and untreated. Candida, Aspergillus, and other fungi are part of our microbiome, but under the right conditions (e.g., over-exposure to antibiotics, immune suppression, poor diet), they can overgrow and begin to release mycotoxins directly within the host. Candida fungal species, for instance, can produce ‘Acetaldehyde’ which slowly chokes cells ability to respire – generate energy using oxygen.

This means that even individuals who don’t feel they experience mycotoxin exposure from the environment could still be under chronic internal assault from mycotoxins. These internal producers are even harder to detect – and rarely are they tested for in oncology clinics.

So ask yourself: how many cancer patients are struggling against invisible internal infections that are flooding their systems with immune-disabling and inflammation-causing mycotoxins? And how many of these patients are failing to respond to treatment because their immune system is already too depleted to fight?

Missing the Fungal Factor: A Dangerous Oversight

If practitioners aren’t testing cancer patients for fungal overgrowth or measuring their mycotoxin load, then we are fighting cancer with one eye closed.

This is not conjecture. Evidence such as that provided by Ravid Straussman and colleagues, has shown that fungal pathogens exist within all cancerous tissue, that is, those we have the ability to detect.

So even if you set aside the idea that fungi are actively driving cancer from within – as explained by the Cell Suppression Theory, you cannot ignore the physiological chaos they create through their toxins.

Let’s say it plainly: a patient filled with mycotoxins is a patient under siege. Their immune system is distracted, their inflammatory markers are elevated, and their cellular machinery is under oxidative assault. That is not the state you want a patient to be in when you’re trying to initiate remission, reduce inflammation and help the body return to an optimum level of healing.

Beyond the relevance of Mycotoxins:

My theory – the Cell Suppression Theory – goes one step further than the discussion above.

It proposes that fungal pathogens don’t merely contribute to cancer through their toxins – they may actually cause cancer by hijacking intracellular metabolism. In this model, the fungal pathogen enters the cell, triggers the Warburg effect as part of a coordinated Cell Danger Response, suppresses apoptosis, and manipulates the immune landscape to ensure its survival – all of which happen to mirror cancer's defining traits.

This theory not only accounts for the presence of mycotoxins but explains the deeper biological rationale for why fungal elements are so consistently present in cancer biology. It ties together metabolism, immune evasion, apoptosis suppression, and more into a unified model that the Somatic Mutation Theory (established genetic theory of cancer) has continually failed to offer.

Conclusion: It’s Time to Pay Attention

If you take nothing else from this article, take this:

You don’t need to believe that fungi cause cancer to understand that mycotoxins can significantly contribute to the conditions that allow it to take hold.

We have overwhelming evidence that mycotoxins are toxic, immunosuppressive, and pro-inflammatory. We have increasing evidence that fungi are found within cancer tissue. We have decades of patient cases, overlooked biomarkers, and failed treatments that all whisper the same truth: We are missing something.

And maybe that something isn’t genetic. Maybe it’s fungal.

At the very least, fungal involvement in cancer should be at the forefront of any strategy to combat the disease – if not because of their possible role in its origin, then because of their toxic, inflammatory, and immune-disabling by-products that could be quietly sabotaging treatment outcomes.

And in light of the growing evidence supporting the Cell Suppression Theory, perhaps it's time we gave the fungal connection the serious attention it deserves.

I've read your book. Powerful info! I started reading about cancer their when my sister in law was dx with breast cancer mets to lymph and spine. Became familiar with Warburg effect and Dr Seyfried metabolism theory. After reading your research I really feel like so much progress of knowledge has been made.

Have you followed any of Italian Dr. Tullio Simoncini's suppositions and procedures? His claimed success was attacked by his peers, but with dramatic testimonies, still should be considered.